Bringing medicine to the streets

A newly formed street medicine fellowship is allowing academic centers and cities to bring care to homeless patients instead of waiting for them to present to a hospital or shelter.

There may be no place like home, but more than half a million people in this country don't have one. And because people experiencing homelessness don't connect with health care systems very well, some physicians and other clinicians are reaching out to them directly.

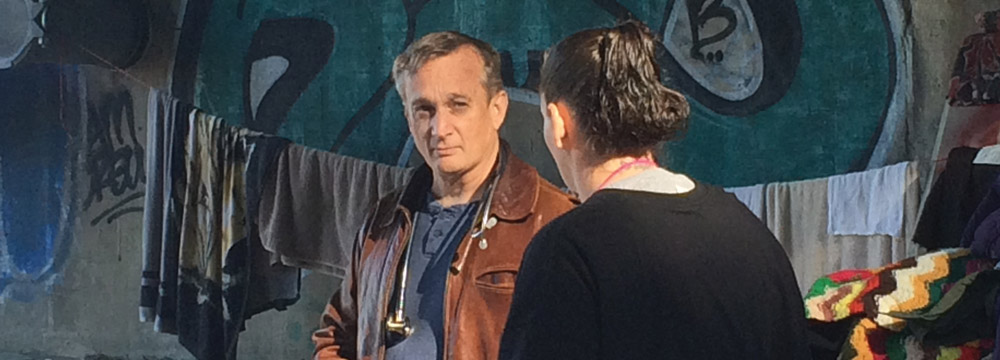

As part of a movement called street medicine, teams of physicians, students, and outreach specialists go to campsites and under bridges, providing direct patient care and following those who need to go to the ED or hospital. In addition to caring for the homeless wherever they are, street medicine programs train medical students and residents outside of the traditional four walls of clinics and hospitals. Longtime street medicine practitioner and educator James S. Withers, MD, FACP, calls it “a classroom of the streets.”

He founded the Street Medicine Institute in 2009, and its student coalition now represents about 35 medical schools in the U.S. and Puerto Rico that reach out directly to people experiencing homelessness. During his 30 years on the faculty at UPMC (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center) Mercy and its predecessor, The Mercy Hospital of Pittsburgh, Dr. Withers has taught fourth-year medical students during a one-month elective at Pittsburgh Mercy Family Health Center, where he is founder and medical director of Pittsburgh Mercy's Operation Safety Net. The latter program has provided medical and social service outreach to people experiencing homelessness in Pittsburgh and greater Allegheny County, Pa., for the last 26 years.

“I would regard [Dr. Withers] as the founder of the street medicine movement,” said A.J. Pinevich, MD, FACP, vice president of medical affairs for UPMC Mercy.

What started as Dr. Withers' personal interest in street medicine has expanded to become a broader movement to bring health care directly to people in the U.S. and beyond. His latest effort is launching the first known street medicine fellowship in July 2019. The one-year, nonaccredited fellowship is a partnership between Pittsburgh Mercy, which will serve as the fellowship's primary clinical classroom for experiential learning, and UPMC Mercy, the main sponsor and acute care-based academic host. “I think the traditional attitude has been, ‘Well, if people who are homeless want care, why don't they come to us?’ which, to me, shows a lack of empathy and, frankly, a lack of curiosity,” Dr. Withers said. “More and more academic centers and cities have begun to not wait for people to come to them.”

Earning trust

About 553,000 people in the U.S. experienced homelessness on a given night in 2018, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Point-In-Time Count. While nearly two-thirds of them were staying in sheltered locations, 35% were in unsheltered locations.

In Boston, these so-called “rough sleepers” have an all-cause mortality rate that is almost 10 times higher than that of the general Massachusetts population and nearly three times higher than that of a homeless cohort who slept primarily in shelters, according to a study published in September 2018 by JAMA Internal Medicine.

When senior author James J. O’Connell, MD, FACP, finished residency in 1985, he immediately began to work as the initial physician for Boston's brand-new Health Care for the Homeless Program. Each year, the citywide program cares for more than 12,000 different homeless men, women, and children in Boston, he said.

The program focuses heavily on continuity of care, from the streets and shelters through the hospital and into respite care, which was created by the program in September 1985, said Dr. O’Connell, who is president of the program and an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The model of care includes daily clinics at two hospitals (as well as a network of clinics held in shelters and soup kitchens), a 124-bed medical respite program, inpatient rounds, house calls to formerly homeless people, daytime street rounds, and a nightly van serving soup, sandwiches, clothing, and blankets, he said. Dr. O’Connell has served as the doctor on the van, which is run by a local shelter, two days a week since it first launched 34 years ago.

As the program began, it became apparent that care on the streets was essential. In 1985, a multidrug-resistant tuberculosis outbreak and the AIDS epidemic ravaged the homeless community, so the group responded by going not only into the shelters but onto the streets, Dr. O’Connell said.

“The dictum for us was, if you wait for people to come to you, in the hospital or the emergency room, it's too late,” he said. “So you have to go out and find people wherever they are, especially the people who are struggling just to survive day to day.” These days, the street team includes two internists, a psychiatrist, a nurse practitioner and/or physician assistant, a social worker, and a recovery coach, all working full-time caring for Boston's roughly 700 current or former street folks, Dr. O’Connell said.

But it's not enough to simply go out to people on the street. Clinicians must take the time to really get to know them and earn their trust before they can even take a history and physical, he said. “You can't rush. You have to be patient, have cups of coffee, do all the things that are not very valued, certainly during residency, and … wait for them to open up,” said Dr. O’Connell. “Because unless you get that relationship, you're never going to make headway with any primary or specialty care.”

A common theme with street medicine programs is having an outreach worker, often one who's experienced homelessness, to guide clinical teams and help solidify trust. In Los Angeles, Brett Feldman, MSPAS, PA-C, started a street medicine program in April 2018 that has a street guide who “knows the streets more than anybody,” helps guide teams to where patients are, and keeps the process safe and efficient.

Earning patients' trust often comes down to small acts of kindness, such as riding the bus with them and enduring harassment from other passengers because of how they look or smell, he said. “The key to being successful in street medicine is your willingness to share in the patient's suffering, but do so with this unending joy so that they know you're willing to go through certain things with them,” said Mr. Feldman, adding that street medicine urges clinicians to get below eye level with the patient in a servant's posture. “The person that has the position of authority is the patient.”

Completing the transition includes hospital consults, which are still a pillar of street medicine, said Dr. Withers. While clinicians in his program at Pittsburgh Mercy's Operation Safety Net spend most of their time visiting homeless patients, they also go to hospitals, EDs, and follow-up appointments with them to humanize the experience. “We bring information to the team in the hospital that they don't have and bring a level of trust and cooperation,” he said. “And then together, with the individual, we create a person-centered, reality-based discharge plan.”

A foreshadowing of epidemics

The situation in Los Angeles is in stark contrast to that in Boston, which has robust shelters and open beds. Los Angeles has by far the most unsheltered homeless people in the country, said Mr. Feldman, director of street medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California and vice chair of the Street Medicine Institute. “We have about 40,000 unsheltered homeless: 52,000 total but 40,000 on the street … and there's nowhere for them to go. The shelters are completely full,” he said.

Mr. Feldman, who recently moved to Los Angeles from Pennsylvania, said he has seen conditions he was not expecting, such as hepatitis A virus infection, a typhus outbreak, tuberculosis, full-blown AIDS, and measles. This past winter, he saw frostbite twice and had a patient admitted to the ICU for hypothermia. “The worst frostbite [cases] we see are usually temperatures in the high 30s with rain because they're not prepared for it,” he said.

As Dr. O’Connell observed in the 1980s, people who are homeless tend to be predictors of what's coming, such as the AIDS epidemic and the opioid epidemic, Mr. Feldman said. “They're like the stress test on the system. … There's a lot that we can learn about what's coming from what's happening on the streets,” he said.

Research from Dr. O’Connell's group in Boston has found that the causes of death among the city's homeless changed significantly over a 15-year period. There was a threefold increase in drug overdose deaths and a twofold increase in suicide deaths from 1988-1993 to 2003-2008, leading to an 83% higher rate of deaths due to external causes, according to results published in February 2013 by JAMA Internal Medicine. “For the first time in our history, cancer was no longer the leading cause of death among homeless people, but it was opioid overdose … and opioids had overtaken alcohol as the most commonly used drug on the streets,” said Dr. O’Connell.

At the same time, the homeless population experiences the full spectrum of bread-and-butter internal medicine problems, such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, said ACP Member Tim Mercer, MD, MPH, assistant professor of population health and internal medicine at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin and a primary care physician with Austin's Health Care for the Homeless program, part of the federally qualified health center network called CommUnityCare. “You name it, we see it. … Much of it is later-stage, poorly managed, or complications because of access-to-care issues in the past,” he said.

Still, there are differences between street medicine patients and those typically managed in internal medicine primary care. First of all, there is a huge burden of comorbid psychiatric illness and/or substance use disorders, said Dr. Mercer, who is project director for the school's grant-funded mobile care team, which targets the unsheltered homeless population and works with outreach partners to integrate medical care with behavioral, mental, and social health care.

In addition, many patients on the street have hepatitis C virus infection, cirrhosis, musculoskeletal conditions, and pain, he said. “Living on the streets is hard on your body. Rough sleeping takes a toll on your back, on your hips, on your knees, on your skin, on your feet,” said Dr. Mercer. Plus, limited access to subspecialty physicians means that he sometimes manages patients he might have otherwise referred. “I manage a fair number of patients with seizure disorders because it takes a long time to get in to see a neurologist,” he said.

Working against siloed systems is difficult. Even with excellent medical care, patients facing homelessness are up against a host of other fundamental issues, such as poverty and housing, which can be discouraging for physicians, Dr. Mercer said. “I can get their blood pressure perfect and bring their A1c to goal, have them on all the evidence-based therapies for their medical conditions, but if we're not addressing the root causes of homelessness and poverty at a policy level, then we're kind of spinning our wheels a little bit,” he said.

Dr. O’Connell agreed, adding that there are many systems in this country that contribute to the problem. “If you looked at homelessness as a prism held up to society, what you would see refracted are the weaknesses in all of the sectors, particularly education, welfare, foster care, corrections or justice, housing, and health care,” he said.

While some states, like Massachusetts, have expanded Medicaid to help cover the poorest of the poor, others, like Texas, rely on county- or city-based programs to expand access to coverage. In Austin, the Medical Access Program is a safety-net insurance program that covers primary care services for many of Dr. Mercer's patients. “Most basic medications are covered, such as hypertension medicines, insulin, and basic lab tests as well,” he said, adding that he uses a mobile hotspot and his laptop to write prescriptions in the electronic health record.

Teaching the next generation

While caring for the homeless can be depressing and daunting, it is extremely rewarding overall, said Dr. Mercer, who has medical students and residents rotate with him in the clinic and on the street. “Helping train the next generation of the workforce is also really important to what I do and gives me a lot of meaning,” he said.

At Dell Medical School, a new school that is just welcoming its fourth class, students do a two-year longitudinal primary care clerkship during their second and third years. In addition, internal medicine interns also rotate in the shelter-based clinic and community-based sites on the street during their ambulatory block. “Our students are hungry for doing things differently and finding new approaches to care. … They also realize that we're teaching good old-fashioned internal medicine in this context too,” he said.

Addressing both components is important because internal medicine residents tend to spend much of their time in the hospital, which only offers one view of this complex patient population, Dr. Mercer added. “We know that individuals experiencing homelessness are sick and complex and have disproportionally higher rates of hospitalization and ED utilization, so I think giving [residents] that exposure to taking care of that population on the outpatient side and trying to keep them out of the hospital has been a really impactful approach,” he said.

In Pittsburgh, where the homeless aren't allowed to sleep downtown, they retreat to more remote areas, and Dr. Withers' team follows. The team consists of about four to five members on a typical day, including an outreach worker, a couple of students, and at least one licensed clinician, such as a volunteer or retired doctor. Typically, the team parks near a campsite and walks to the area with their backpacks. If the outreach person determines it's a good day to visit, he waves the team into the camp. “We try to assess the immediate needs,” said Dr. Withers. “Usually we distribute socks, sandwiches, or water bottles, and almost always they'll say, ‘Hey, can you look at this?’ and they'll pull up their pants leg or something.”

Notes are taken on paper, and this is where the trainees often shine. “One of the things that actually helps a lot has been students, because if they're not real sure of exactly what to say, we usually assign them the role of a scribe,” he said.

Students and residents are particularly interested in street medicine for humanist reasons, said Dr. Withers. “It seems like they're getting back something that was so fundamental to why they wanted to go into health care. Many times, they've said, ‘This is the best part of my medical training I've had,’” he said.

Before medical school, Brianne R. Feldpausch, a third-year medical student at the Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine in East Lansing, Mich., trained under Dr. Withers in Pittsburgh. She went on to found Spartan Street Medicine, a program at the medical school that is now run by more than 150 student volunteers with faculty attending physicians. “What we see in the medical office is only one snapshot of one moment of time in what is going on with anyone,” said Ms. Feldpausch. “In street medicine, we take a step outside into their reality.”

Dr. Withers is now beginning to work with his first street medicine fellow, a family medicine-trained physician, as part of the fellowship, which is open to those trained in internal medicine, family medicine, and emergency medicine. About 80% of the year-long fellowship will be clinical, experiential learning work, mostly in the homeless campsites and primary care clinics, but also hospital consults, he said. The rest of the time will be spent helping define street medicine best practices and next steps.

The program was encouraged and supported in large part by UPMC Mercy, namely hospital president Michael Grace, said Dr. Pinevich. “He shepherded the approval of this fellowship on the administrative end because he recognized the potential benefits of physicians who possess this unique type of education, giving back not just to the Pittsburgh community but also communities elsewhere in the U.S. and beyond,” he said.

Beyond the U.S., the Street Medicine Institute has held the International Street Medicine Symposium since 2005, when it was presented in Pittsburgh to a grand total of 17 non-Pittsburghers, Dr. Withers said. Now, more than 200 programs have launched across the world. This fall, from Oct. 21 to 23, 15th annual International Street Medicine Symposium will come back to Pittsburgh for the first time, and he's expecting more than 500 attendees.

The growth of street medicine demonstrates how medicine is moving outside of traditional structures into the reality of the people, said Dr. Withers. “We are so locked, currently, into that white lab coat and the structure of health care as a business that I see this as an act of defiance to reclaim our profession,” he said. “I am just really grateful to the street folks for teaching us.”